What is the hydraulic power transmission system?

A hydraulic power transmission system expertly uses pressurized fluid. It transmits power and motion effectively. This system converts mechanical energy into fluid energy, then transforms fluid energy back into mechanical energy. This enables efficient force and movement transfer. The market for hydraulic transmission systems demonstrates robust growth, with experts projecting a 5.4% CAGR for hydraulic power units from 2025 to 2035.

Key Takeaways

- Hydraulic systems use pressurized fluid to move things. They change mechanical energy into fluid energy, then back to mechanical energy.

- Key parts of a hydraulic system include pumps, actuators, control valves, and special fluid. Each part helps the system work well.

- There are two main types: hydrostatic systems offer precise control, while hydrodynamic systems use fluid movement for power.

Understanding Hydraulic Transmission

How Hydraulic Transmission Works

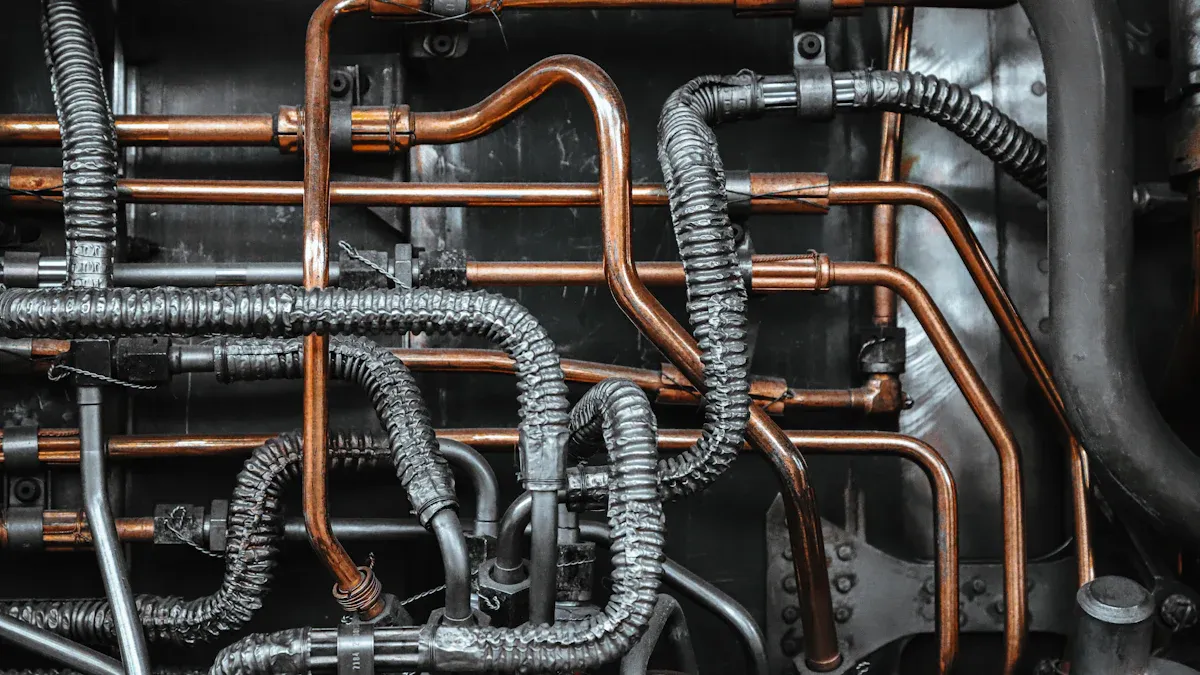

A hydraulic power transmission system operates through a series of energy conversions. It begins when a hydraulic pump takes mechanical energy and transforms it into liquid pressure energy. This pressurized fluid then travels through the system. Hydraulic control valves and various accessories manage this pressure energy. These components precisely regulate the pressure, flow, and direction of the hydraulic fluid. Ultimately, this controlled pressure energy reaches an actuator. The actuator then converts the liquid pressure energy back into mechanical energy. This final conversion performs the desired action, such as lifting a heavy load or moving a component. This entire process demonstrates the efficient energy transfer inherent in hydraulic transmission.

Principles of Fluid Power Transmission

Hydraulic power transmission fundamentally relies on Pascal’s law. This principle states that any pressure applied to a fluid within a closed system transmits equally throughout the fluid in all directions. This unique property allows a small force applied at one point to generate a much larger force at another point. Consequently, hydraulic systems can move heavy objects with relative ease. Hydraulic systems utilize incompressible fluids as their working medium. These fluids effectively transmit pressure without significant volume change, which is crucial for the system’s efficiency and responsiveness. Understanding these principles is key to appreciating the power and versatility of hydraulic transmission.

Key Components of a Hydraulic Transmission System

A hydraulic power transmission system relies on several interconnected components. Each component performs a specific function. Together, they ensure efficient and controlled power transfer.

Hydraulic Pump

The hydraulic pump initiates the power transmission process. It converts mechanical energy from a prime mover, like an electric motor or engine, into hydraulic energy. This energy takes the form of pressurized fluid flow. Various types of hydraulic pumps exist, each suited for different applications.

- Gear Pumps: These are simple and cost-effective. They use two meshing gears to trap and move fluid. Gear pumps are suitable for low-pressure systems and low-flow applications, such as lubrication and cooling. Modern designs incorporate features like split gears and improved tooth profiles. These features reduce noise and smooth operation. Gear pumps exhibit gradual wear, which slowly reduces volumetric efficiency. This provides a warning before catastrophic failure.

- Vane Pumps: These pumps feature a rotor with sliding vanes. The vanes create a vacuum, drawing in and pressurizing fluid. Vane pumps handle higher pressures and thicker fluids. They find common use in mobile applications, like forklifts and dump trucks, and industrial settings, such as plastic injection molding.

- Piston Pumps: These are the most complex type. Pistons move inside a cylinder to create fluid flow. Piston pumps deliver high pressures and flows. They are often used in heavy-duty applications, including mining and construction. Piston pumps can offer variable displacement. They are more expensive and require more maintenance. However, they provide high efficiency and durability for demanding high-pressure and high-flow needs.

- Other Types: Other pumps include Gerotor pumps, Axial Piston pumps (swashplate or bent-axis), Radial Piston pumps, and Screw pumps. Non-positive displacement pumps, like centrifugal pumps, are also relevant in some fluid power systems. Centrifugal pumps impart kinetic energy to the fluid through a rotating impeller. This increases fluid velocity, which then converts to pressure. They are suitable for high-flow, low-to-moderate pressure systems.

Hydraulic Actuators

Hydraulic actuators convert the fluid’s hydraulic energy back into mechanical energy. This mechanical energy performs work. Actuators generate force or motion. They are the “muscle” of the hydraulic system.

- Linear Actuators: These are also known as hydraulic cylinders. They provide force or motion in a straight line.

- Rotary Actuators: These generate torque or rotational motion. They are referred to as hydraulic motors. They achieve constant angular movement.

- Semi-rotary Actuators: These actuators are designed for partial angular movements. This can include multiple complete revolutions, though typically 360 degrees or less.

Hydraulic actuators are very powerful. They generate large forces. This makes them ideal for high-force applications in construction or manufacturing. They also offer high speed. They move very quickly in applications where speed is crucial. Actuators produce tremendous power relative to their physical size. They deliver forces significantly exceeding pneumatic and many electric alternatives. This enables compact designs for heavy-duty applications. Even modest-sized hydraulic cylinders generate tremendous forces. Rod-type units produce up to 5,000 pounds per square inch.

| Characteristic | Capability |

|---|---|

| Peak Power | Very high |

| Speed | Moderate (Slow to High, inversely correlated with force) |

| Load Ratings | Very high |

Actuators are widely used in heavy-duty applications. These include large construction machinery, marine propulsion, cargo handling, military weapons, and transportation systems. They are particularly useful in tasks requiring significant power.

Control Valves

Control valves manage the hydraulic fluid within the system. They regulate the fluid’s direction, pressure, and flow rate. This ensures the system generates usable power.

- Directional Control Valves: These valves initiate, pause, stop, and alter the direction of fluid flow. They are also known as switching valves. Their design is identified by the number of working ports and spool positions.

- Pressure Control Valves: These valves release excess pressure from the hydraulic system. Their functions include relief, reduction, sequencing, counterbalancing, and unloading. They prevent issues like leakage or burst pipes. Examples include pressure-reducing valves, which limit clamping pressure, and unloading valves, which divert pump delivery to the reservoir. Sequence valves control sequential operations. Counterbalance valves maintain backpressure to prevent uncontrolled movement.

- Flow Control Valves: These valves regulate the flow rate. This adjusts the speed of an actuator. They also influence the rate of energy transfer at a given pressure level. They prevent backflow. Flow control valves come in various models, such as fixed flow, adjustable flow, and pressure-compensated flow control. Simple valves like ball valves use a rotating ball to align or obstruct the flow path. Butterfly valves use a rotating plate. Needle valves offer more precise control with an adjustable needle.

In hydraulic circuits, the pump generates flow, not pressure. Pressure results from resistance to fluid flow within the system. Flow rate determines the speed of actuators. Pressure enables the exertion of force.

Hydraulic Fluid

Hydraulic fluid is the medium for power transmission. It transfers energy throughout the system. The fluid must possess specific properties for optimal performance.

- Key Properties: Hydraulic fluid must be non-compressible. It needs a high bulk modulus. It should have fast air release and low foaming tendency. Low volatility is also important. For heat transfer, it requires good thermal capacity and conductivity. As a sealing medium, it needs adequate viscosity and a high viscosity index. It also requires shear stability. For lubrication, it needs proper viscosity for film maintenance, low-temperature fluidity, and thermal and oxidative stability. It also needs hydrolytic stability, water tolerance, cleanliness, filterability, anti-wear characteristics, and corrosion control.

- Classifications:

- HL (Hydraulic Oils with Anti-Rust and Anti-Oxidation Properties): These offer anti-rust protection and anti-oxidation. They are used in general-purpose hydraulic systems with moderate operating conditions.

- HM (Hydraulic Oils with Improved Anti-Wear Properties): These provide enhanced wear protection, anti-rust, and anti-oxidation. They are critical for high-pressure and high-load hydraulic systems.

- HH (Non-Inhibited Refined Mineral Oils): These offer basic lubrication. They lack anti-rust or anti-oxidation additives. They are used in systems where additional protection is not needed.

- HR (HL Oils with Viscosity Index Improvers): These have viscosity index improvers for consistent performance across temperatures. They combine HL properties. They are used in hydraulic systems exposed to varying temperatures.

Environmental and safety considerations are crucial for hydraulic fluids. Petroleum-based fluids are non-biodegradable and toxic. They pose fire risks and can irritate skin and respiratory systems. Environmentally friendly hydraulic fluids are readily biodegradable and non-toxic. They have higher flash points, reducing fire hazards. They are safer to handle and dispose of. Proper training, personal protective equipment, and safe storage are essential when handling any hydraulic fluid. Spills require immediate cleanup due to slip hazards and potential environmental harm.

Reservoir and Filters

The reservoir stores the hydraulic fluid. It also conditions the fluid. It facilitates cooling, contaminant settling, and the removal of entrained air and water vapor. Filters maintain fluid cleanliness.

- Reservoir Design: Reservoirs serve as a central fluid source. They supply the pump and receive return flow. Reservoir selection depends on specific customer requirements. Common designs include horizontal and overhead. Materials like stainless steel or aluminum are available for specialized applications. For most industrial applications, the minimum reservoir size should be approximately 2.5 times the pump’s flow rate. A general rule of thumb suggests a volume of 3 to 4 times the pump’s flow rate. This allows for heat dissipation, contaminant settling, and deaeration.

- Venting: Reservoirs must breathe. They require a vent or breather cap. Improper venting starves the pump and damages the reservoir.

- Return Oil Flow: Returning oil should enter the tank below the oil level. This prevents foam and air bubbles.

- Port Placement: Pump inlet and return ports should be on opposite ends. This allows returning oil to cool.

- Baffles: Baffles keep warmer return oil away from the pump inlet. They prevent sloshing.

- Materials: Steel is strong and durable. Aluminum is lightweight and corrosion-resistant. Plastic is lightweight and moldable but not suitable for high temperatures or pressures.

- Features: Reservoirs incorporate sight glasses, fluid level indicators, and breathers. A drain valve is typically included for easy draining and cleaning.

- Filters: Filters remove contaminants from the hydraulic fluid. This protects system components and extends fluid life.

- Filter Media:

- Micro-fiberglass (microglass): Used for fine filtration. They are strong and efficient but not reusable.

- Steel wire mesh: Used to capture larger particles. They are often used for strainers. They can be cleaned and reused.

- Cellulose (paper filters): Inexpensive but less effective. They can lead to significant pressure drop.

- 80/20 Cellulose + Polyester: A blend that overcomes pressure drop issues and lasts longer.

- Filtration Ratings:

- Micron Rating: This refers to the smallest particle size a filter can capture. Higher micron ratings indicate coarser filtration. Smaller ratings mean finer filtration.

- Absolute Rating: This is the diameter of the largest spherical glass particle that will pass through the filter. It reflects the pore opening size.

- Nominal Rating: This indicates a filter’s ability to prevent the passage of a minimum percentage of solid particles greater than the stated micron size.

- Beta Ratio: This is a newer test procedure. It provides an accurate comparison between filter media. A higher Beta Ratio indicates higher efficiency.

- ISO Cleanliness Codes (ISO 4406): This standard quantifies contamination levels. It uses three numbers (e.g., 18/16/13). These numbers indicate particles per milliliter at specific micron sizes. Maintaining appropriate ISO cleanliness levels is crucial for system performance and longevity.

- Filter Media:

Types of Hydraulic Transmission

Hydrostatic Transmission

Hydrostatic transmission systems utilize fluid pressure to transfer power. They offer precise control over machine speed and direction, making them ideal for fine adjustments. These systems provide infinitely variable speed control, allowing smooth adjustments from zero to maximum without requiring gear shifts. This enhances operator comfort by eliminating the need for gear changes and ensuring smooth operation, which reduces fatigue. Hydrostatic transmissions excel in low-speed, high-torque applications where mechanical transmissions often struggle. They integrate with electronic control systems for automatic grade control, load management, and effective power distribution. This allows for programmable custom speed curves and response characteristics to match specific application requirements.

Hydrostatic transmissions are particularly useful in construction equipment like excavators, loaders, and bulldozers, where they provide precise handling of heavy loads. Agricultural machinery, such as tractors and harvesters, also employs them for smooth and controlled power delivery. Specialized vehicles like forklifts and industrial machinery benefit from hydrostatic systems, enhancing performance and maneuverability, especially for tasks requiring on-demand bursts of power and operation at low speeds.

Hydrodynamic Transmission

Hydrodynamic transmission systems, in contrast, use the kinetic energy of fluid to transmit power. They primarily employ a hydraulic torque converter, which consists of a pump, a turbine, and a fluid-filled housing. While hydrodynamic systems are very efficient, boasting up to 98% conversion rates, they are less flexible than hydrostatic systems. Adjusting speed and torque is more difficult with hydrodynamic transmissions. They can also be bulky and heavy, particularly in high-power applications. However, they operate very quietly, especially at high speeds.

| Feature | Hydrostatic Transmission | Hydrodynamic Transmission |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages | - Very efficient (up to 90% conversion rates) - Very flexible, easily adjustable speed and torque |

- Very efficient (up to 98% conversion rates) - Very quiet, especially at high speeds |

| Disadvantages | - Can be expensive to manufacture and maintain - Can be quite noisy, especially at high speeds |

- Can be bulky and heavy, especially in high-power apps - Not very flexible, difficult to adjust speed and torque |

| Mechanism | Uses hydraulic pump and motor to transfer power | Uses a hydraulic torque converter (pump, turbine, fluid-filled housing) |

| Control | Speed and torque controlled by adjusting fluid flow/pressure | Speed and torque determined by torque converter characteristics |

Hydraulic power transmission systems are fundamental for transmitting force and motion across various applications. They operate by converting and transferring energy through pressurized fluid. Understanding their components and types is crucial for appreciating their widespread utility. These systems offer robust solutions for diverse industrial needs, providing efficient and controlled power.

FAQ

What are the primary benefits of hydraulic power transmission systems?

Hydraulic systems offer high power density, precise control, and the ability to transmit large forces. They also provide smooth operation and inherent overload protection.

Where do hydraulic systems find common applications?

Industries widely use hydraulic systems in construction, manufacturing, aerospace, and marine sectors. They power heavy machinery, industrial presses, aircraft controls, and ship steering mechanisms.

How do hydrostatic and hydrodynamic transmissions differ?

Hydrostatic systems transfer power using fluid pressure, enabling precise control. Hydrodynamic systems utilize fluid kinetic energy, primarily for torque conversion, and offer less flexibility.