What are the five major components of a hydraulic system?

The five major components of a hydraulic system are the reservoir, pump, valves, actuators, and hydraulic fluid. Each component plays a distinct and crucial role in the system’s operation. Understanding these parts is fundamental to comprehending how hydraulic power is generated and utilized. The global hydraulic systems market, valued at USD 44.08 billion in 2024, projects a 2.8% Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) from 2025 to 2033.

Key Takeaways

- A hydraulic system has five main parts: a reservoir, a pump, valves, actuators, and hydraulic fluid. Each part does a special job to make the system work.

- The hydraulic pump changes mechanical energy into fluid power. This power then moves actuators, which do the actual work like lifting or pushing.

- Hydraulic fluid is very important. It moves power, keeps parts lubricated, and helps cool the system. This makes sure the system runs well and lasts a long time.

The Reservoir in a Hydraulic System

Storing Hydraulic Fluid

The reservoir serves as the primary storage unit for hydraulic fluid within a hydraulic system. It holds the necessary volume of fluid to accommodate system demands, including fluid expansion from heat and changes in actuator position. This component ensures a continuous supply of fluid to the pump, preventing cavitation and maintaining system integrity. A properly sized reservoir is crucial for efficient operation.

Dissipating Heat

Beyond storage, the reservoir plays a vital role in heat dissipation. The large surface area of the reservoir allows heat to radiate into the surrounding environment, cooling the hydraulic fluid. Maintaining optimal fluid temperature is essential for system longevity and performance.

| Fluid Type | Typical Operating Temperature Range |

|---|---|

| General Hydraulic Fluid | 100°F (38°C) to 140°F (60°C) |

| AW 32 Hydraulic Oil | -11°F to 413°F |

| ISO 46 Hydraulic Oil | 25°F to 70°F (-4°C to 21°C) |

| ISO 68 Hydraulic Oil | Up to 140°F (for 100% life) |

Hydraulic oil begins to break down around 140°F (60°C). Significant system damage can occur at approximately 180°F (82°C). Effective heat management prevents fluid degradation and component wear.

Controlling Contaminants

The reservoir also acts as a settling tank, allowing heavier contaminants to settle at the bottom. This process helps keep the fluid clean. Modern hydraulic systems employ various filtration methods to further control contaminants.

- Multi-stage filtration addresses different types and sources of contamination.

- Return line filtration captures wear particles before recirculation.

- Pressure line filtration protects sensitive components like servo valves.

- Kidney loop filtration systems continuously filter fluid from the reservoir, often removing water.

- Breather filtration prevents atmospheric particles and moisture from entering the system.

High-quality hydraulic filter elements, offline filtration units, and breathers are crucial for maintaining fluid cleanliness. These measures protect components and extend the life of the entire hydraulic system.

The Hydraulic Pump: Powering the System

Converting Mechanical to Hydraulic Power

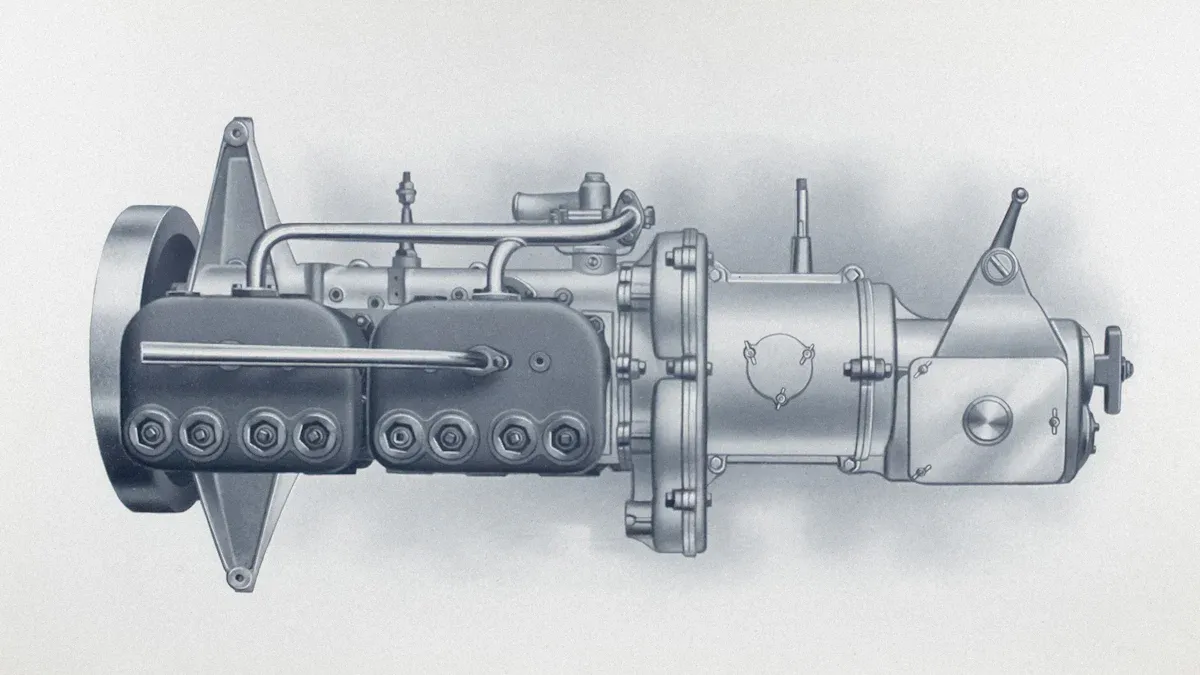

The hydraulic pump acts as the heart of any hydraulic system. It converts mechanical energy, typically from an electric motor or engine, into hydraulic energy. This conversion happens by creating fluid flow. The pump draws hydraulic fluid from the reservoir and pushes it into the system under pressure. This pressurized fluid then drives the actuators to perform work. A pump’s overall efficiency measures its ability to convert energy. High-quality piston pumps can achieve around 95% efficiency, significantly higher than older gear pumps. This efficiency reduces waste and cooling requirements.

Common Types of Hydraulic Pumps

Various types of hydraulic pumps exist, each suited for different applications. Gear pumps are common for their simplicity and robustness. They find use in hydraulic power systems, high-pressure hydraulic systems, and applications like dump trucks. Gear pumps also excel at handling high-viscosity fluids such as oil, paints, and resins. Piston pumps offer higher efficiency and pressure capabilities. They are crucial in mining operations for heavy-duty tasks and in automotive applications like power steering. Piston pumps also power precise movements in robotics and ensure reliability in aerospace landing gear systems. They are widely used in construction equipment, agricultural machinery, and industrial equipment like injection molding machines.

Key Pump Performance Factors

Several factors define a hydraulic pump’s performance. Efficiency is paramount, encompassing volumetric, mechanical, and overall efficiency. Volumetric efficiency measures the actual fluid delivered versus the theoretical flow. For example, a pump delivering 90 liters/minute from a theoretical 100 liters/minute has 90% volumetric efficiency. Mechanical efficiency accounts for energy loss due to friction. Overall efficiency combines these factors. Pump efficiency varies with operating speed; it typically increases to a maximum between 1,000 and 2,000 rpm. Some advanced pumps can achieve peak efficiencies near 96% at optimal speeds. Hydraulic intensifiers can generate extremely high pressures, reaching up to 150,000 psi in specialized pumping systems.

Control Valves in a Hydraulic System

Directing Fluid Flow

Control valves are essential components in a hydraulic system. They guide the flow of hydraulic fluid. Directional control valves (DCVs) determine the path of this fluid. They can start, stop, or change the direction of flow. Their function depends on the number of working ports and spool positions. Common types include 4/3-way valves, which have four ports and three positions. Two-way valves have an inlet and an outlet. Three-way valves are used for single-acting cylinders. They feature an inlet, an outlet, and an exhaust. These valves respond quickly to commands. Servo valves can respond in 5 to 50 milliseconds. Proportional valves typically respond in 50 to 200 milliseconds. Simple on/off valves take 100 to 500 milliseconds. This rapid response ensures precise control over hydraulic operations.

Regulating System Pressure

Control valves also manage pressure within the system. Hydraulic pressure control valves (PCVs) prevent damage to pipes and other components. They maintain set pressure levels. These valves are crucial in almost all hydraulic circuits. Types include relief valves, which limit maximum pressure. Reducing valves lower pressure in specific parts of the circuit. Sequence valves ensure operations occur in a specific order. Counterbalance valves prevent loads from running away. Unloading valves divert pump flow when not needed. Each type serves a specific function in pressure management, ensuring safe and efficient operation.

Controlling Fluid Flow Rate

Control valves regulate the speed of actuators. Hydraulic flow control valves (FCVs) manage the fluid flow rate in a hydraulic circuit. They primarily control the speed of cylinder actuators. They also help optimize system performance by monitoring and adjusting for pressure fluctuations. Direct operated proportional flow control valves typically handle flow rates from 3 to 21 GPM. High-performance servo-proportional valves offer nominal flow ranges from 1 to 1000 LPM. This precise control over flow rate allows for smooth and controlled movement of machinery.

Hydraulic Actuators: Performing Work

Converting Hydraulic to Mechanical Energy

Actuators are the components in a hydraulic system that perform the actual work. They transform the pressurized fluid’s energy into linear or rotary mechanical motion. This mechanical output performs tasks like lifting, pushing, pulling, or rotating. Actuators are the final stage where hydraulic power becomes useful work.

Hydraulic Cylinders

Hydraulic cylinders are linear actuators. They produce force and motion in a straight line. Fluid pressure pushes a piston inside a cylinder barrel. This extends or retracts a rod. Common materials for hydraulic cylinder construction include:

- Primary Materials: Stainless steel, aluminum, bronze, and chrome.

- Barrel: Often cold-rolled or honed seamless steel or carbon steel tubing.

- Glands & Pistons: High-tensile SAE C1026 or St52.3 cold-drawn tubes are standard. Other options include 4140, aluminum, and stainless steel.

- Seals: High-performance polyurethane, nitrile rubber, and fluoro rubber are common.

- Shafts: Chrome-plated, nitrided, or chrome-over-stainless steel options exist.

- Cylinder Mounts: Generally steel, carbon steel, and ductile iron.

- Paint: Epoxy, polyurethane, and chromic oxide protect the exterior.

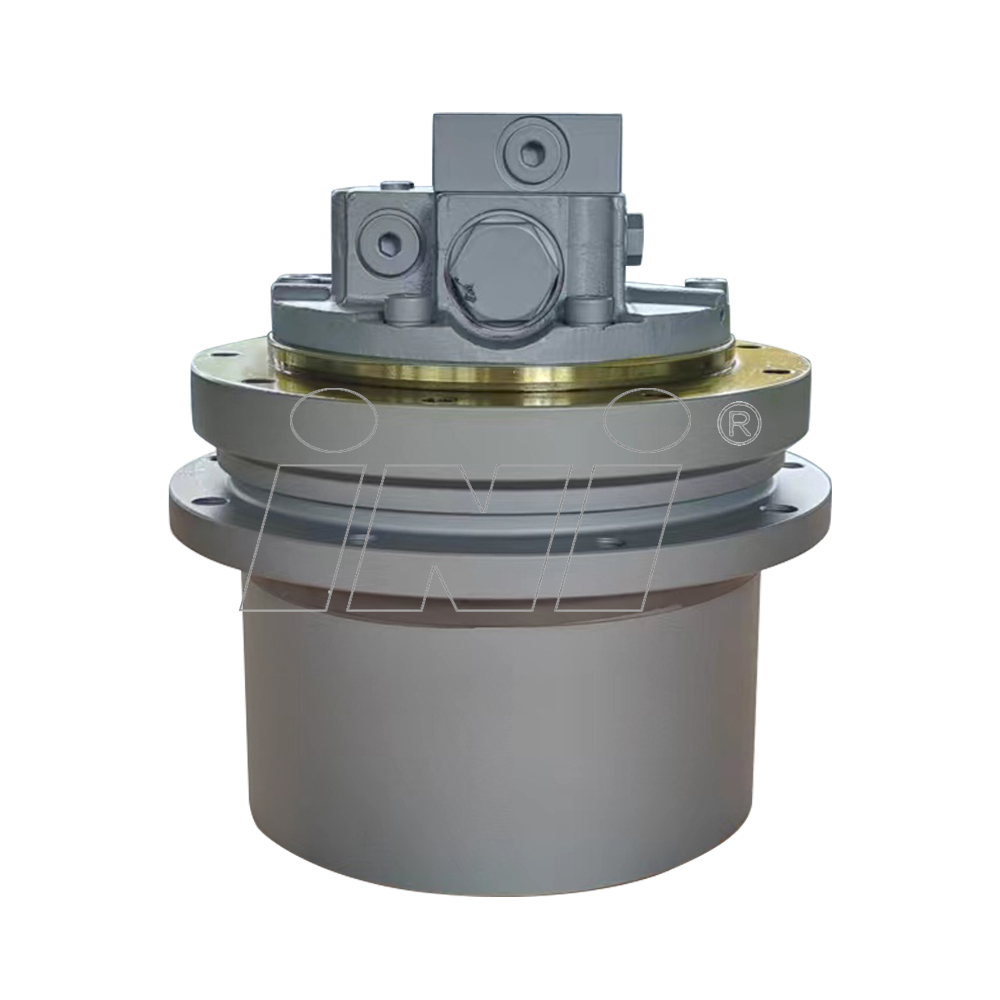

Hydraulic Motors

Hydraulic motors are rotary actuators. They convert hydraulic energy into continuous rotational motion. These motors are essential for applications requiring constant turning force within a hydraulic system. Hydraulic motors operate across various speed ranges:

| Motor Type | Speed Range |

|---|---|

| High speed | above 500 rpm |

| Medium speed | 300–500 rpm |

| Low speed | below 300 rpm |

Achieving speeds below 50 rpm often requires specialized low-speed high-torque (LSHT) hydraulic motors or external reduction devices. A gear-type hydraulic motor illustrates performance. If a 200 RPM speed loss is acceptable from zero to full load at 800 RPM, the maximum adjustable speed range becomes clear. If 800 RPM is the minimum, increasing the top speed allows a wider adjustable range, such as 800 RPM minimum to 2,000 RPM maximum (a 2½:1 range).

Hydraulic Fluid: The Power Transmission Medium

Transmitting Power

Hydraulic fluid serves as the primary medium for power transmission within a hydraulic system. It carries the energy generated by the pump to the actuators. This fluid is incompressible, allowing it to efficiently transfer force and motion. When the pump pressurizes the fluid, it creates a hydraulic force. This force then moves pistons in cylinders or rotates hydraulic motors, enabling the system to perform work. The fluid’s ability to transmit power effectively is fundamental to the entire hydraulic operation.

Lubricating and Cooling Components

Beyond power transmission, hydraulic fluid performs crucial lubrication and cooling functions. It reduces friction between moving parts, preventing wear and extending component lifespan. Anti-wear agents, such as zinc dialkyldithiophosphate (ZDDP), are commonly added to protect hydraulic components from metal-to-metal contact. Friction modifiers also adjust the fluid’s lubricating properties, enhancing smooth operation. The fluid also absorbs and dissipates heat generated by system operation, maintaining optimal operating temperatures for all components.

Essential Fluid Properties

Several properties define a hydraulic fluid’s suitability for an application. Viscosity is critical; it measures the fluid’s resistance to flow. In cold conditions, hydraulic oil needs low viscosity for free flow. Hot environments require higher viscosity to maintain film strength and reduce friction. Multi-grade oils are recommended for systems operating in varying temperatures. Different types of hydraulic fluids exist:

- Mineral-based fluids: Common, inexpensive, and offer good lubrication.

- Synthetic fluids: Provide improved performance in extreme temperatures and high pressures.

- Water-based fluids: Fire-resistant, biodegradable, and low in toxicity.

- Biodegradable fluids: Break down naturally, ideal for environmentally sensitive applications.

Flash point is another important safety property, indicating the temperature at which the fluid vaporizes enough to ignite.

| Hydraulic Fluid Type | Flash Point Range |

|---|---|

| Mineral Oil-Based | 200-250°F (93-121°C) |

| Synthetic | 300-450°F (149-232°C) |

| Water-Based | 300-400°F (149-204°C) |

| Biodegradable | 300-450°F (149-232°C) |

These properties ensure the fluid performs reliably under various operating conditions.

The reservoir, pump, valves, actuators, and hydraulic fluid are indispensable for any hydraulic system. Each component’s proper function is critical for the system’s overall efficiency and reliability. This depends on factors like fluid properties and component quality, which also help prevent common failures such as contamination. Their integrated operation enables the effective transmission and application of power in various industrial and mobile applications.

FAQ

What is the main purpose of hydraulic fluid?

Hydraulic fluid transmits power throughout the system. It also lubricates moving parts and helps cool the components, ensuring efficient and long-lasting operation.

How do hydraulic actuators perform work?

Actuators convert the hydraulic fluid’s energy into mechanical motion. They perform tasks like lifting, pushing, or rotating, making the hydraulic power useful.

Why is the reservoir important for heat management?

The reservoir’s large surface area allows heat to radiate into the environment. This cools the hydraulic fluid, maintaining optimal operating temperatures and preventing fluid degradation.